This article is part of Fast Company’s Lessons of COVID-19 package, exploring some of the ways America has changed since the pandemic hit and what we have learned from it. Click here to read the entire series.

In early March, as the coronavirus was spreading around the world but before it had fully taken hold in the United States, the shortage of ICU ventilators was already becoming a crisis.

Italian hospitals had issued guidelines for rationing ventilators, and experts were concerned that the U.S. stock could quickly be depleted if cases rose at the same rate that they were around the world.

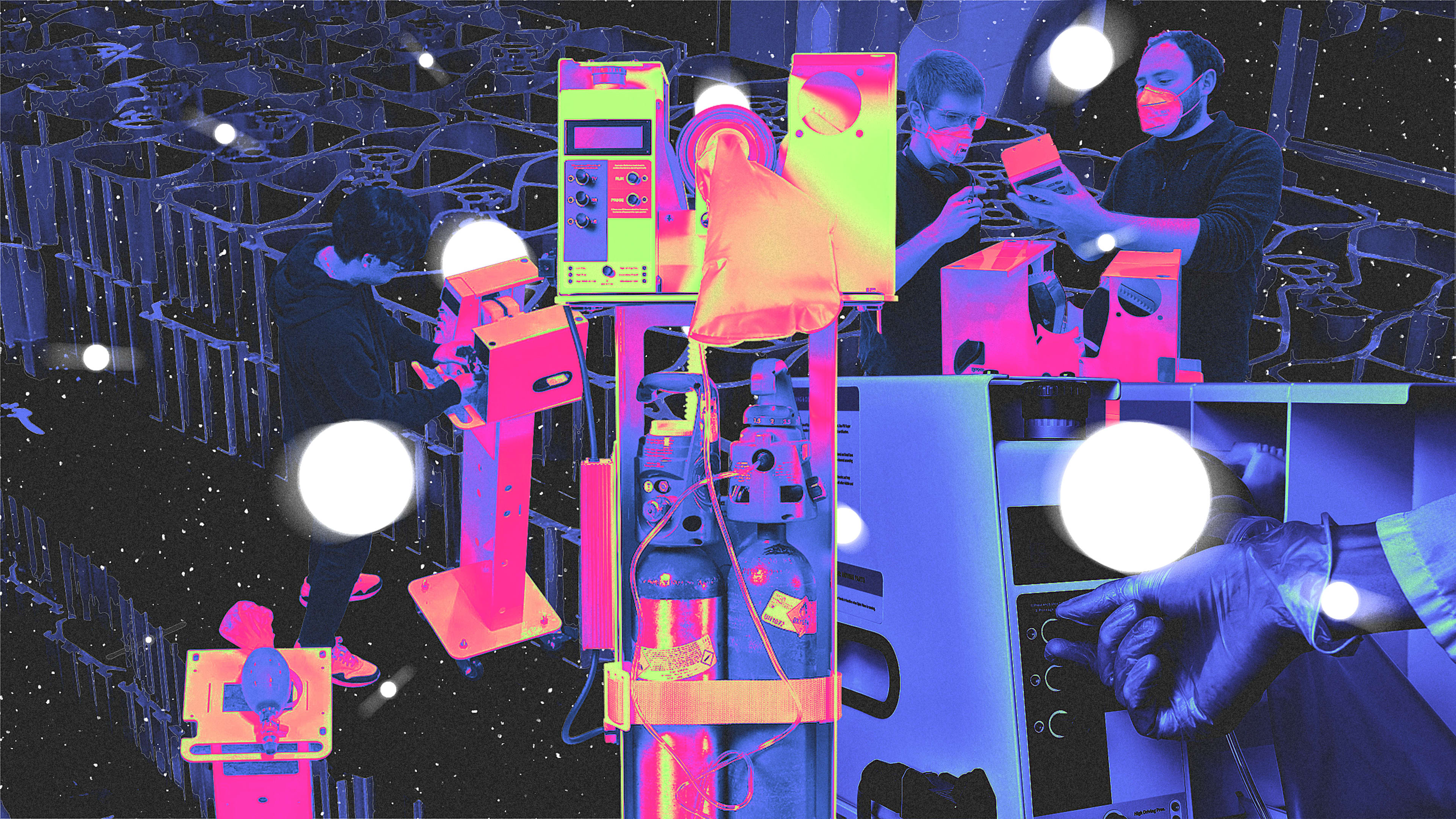

In the midst of the uncertainty and growing panic, a group of entrepreneurs, engineers, and executives teamed up to work on an emergency bridge ventilator. Called the Spiro Wave, the resulting device was developed in under a month, even as New York locked down and supply chains faltered. At the end of that intense push, the group had FDA Emergency Use Authorization and a purchase order from New York City for 3,000 ventilators for the city’s stockpile.

Early March: ‘This is really coming to New York; it’s not us watching a theater’

As the coronavirus devastated Italy at the beginning of March, Scott Cohen and Marcel Botha heard from an Italian colleague in the Netherlands, imploring them to help find a solution to the ventilator shortage. While the men were well-positioned to explore innovative options—Cohen cofounded Newlab and Botha is the CEO of 10XBeta—Cohen wasn’t sure what they could actually do.

“I Googled the ventilator, saw how many parts it took, and said, ‘I don’t know how we can possibly help but we’ll keep paying attention to this.’ he says. “A week went by, and we realized that this is really coming to New York; it’s not us watching a theater.”

As Cohen realized the urgency and started reaching out to his network, a colleague in California suggested he get in touch with Alex Slocum, a mechanical engineer at MIT whose lab was already working on an emergency bridge ventilator. When Cohen asked Slocum if his team could use additional help, he said yes—but what they really needed was an ICU ventilator that they could use as a benchmark.

On Wednesday, March 18, Cohen called Botha to see if he could track one down that they could take to MIT. The dean of Jefferson Medical in Philadelphia was a former client of Botha’s and said he could loan them one. The next day, Botha drove the ventilator up to Cambridge. By then, Cohen and his wife were sick with what they assumed was COVID-19 (testing was still hard to come by at that point), so he was fully remote, fielding logistics from his studio.

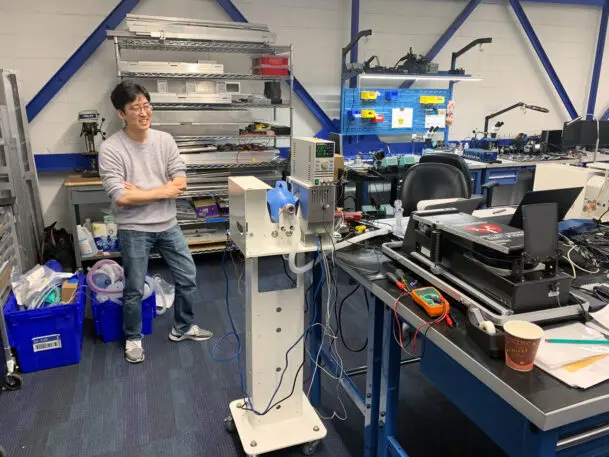

By the 20th, Botha and a colleague were at Slocum’s MIT lab, watching the first side by side test of the ICU ventilator and the one that MIT was developing. “I realized immediately that it would be beneficial if we jumped in and worked with them,” Botha says. His team started working on three different models of the ventilator with MIT, one of which would become the Spiro Wave.

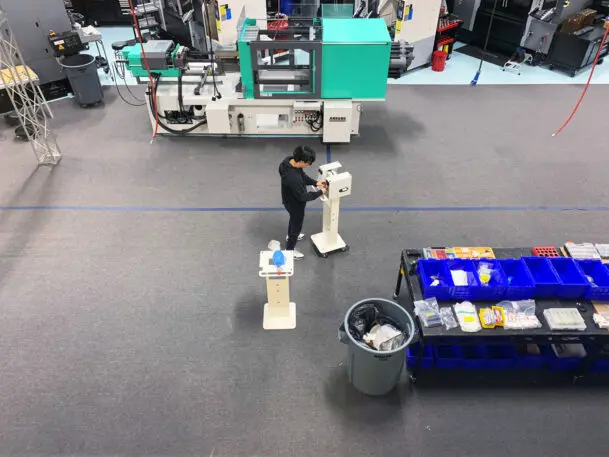

That weekend, a rapidly assembled team built three prototypes at Newlab’s facility. Botha drove back to MIT with the prototypes on Sunday night.

Botha estimates he made between eight and 12 trips to Boston as the prototype was developed over the course of a month. The first few trips, either Botha or a colleague drove, but they quickly realized that was both unsafe and unsustainable. “I was driving too fast and on the phone,” he says. “I feel like I was on the phone 16 hours a day.” After the third trip, they hired a driver.

Mid-March: ‘Anything we took for granted in 2019 we couldn’t take for granted in 2020’

With supply chains upended across the country, it became clear that the team would have to manufacture many components themselves. The week of March 23, the majority of the work migrated over to Boyce Technologies, which has a long-standing relationship with Newlab and is able to design, prototype, and manufacture a range of products on site.

At one point in the process, when the team was testing heavily and going back and forth to MIT, Boyce let them use the company’s Research Rover—a 40-foot RV with a lab and test equipment inside. Eight people could travel in it, which meant the team could continue their work en route.

At that point, people were working essentially nonstop—leaving at midnight, starting shifts in the middle of the night, sleeping under the desks, according to Cohen.

Toward the beginning of the project, there were a number of groups working on different components: Slocum’s lab at MIT, Newlab’s team in New York, as well as a group in California and even one in the Midwest for a time. The operation desperately needed a leader to oversee everything: Cohen stepped up. Through Newlab, which launched in 2016, he’d built a network that extends across the country and encompasses academics, doctors, major corporations, startups, and pretty much any other entity you can imagine. With Spiro Wave, he pulled together teams to handle everything from logistics to regulatory approval to medical feedback.

Late March: ‘Running on fumes’

Almost immediately, Cohen knew that getting FDA approval was going to be a massive hurdle. He eventually connected with Sabrina Varanelli, whose company Nemedio specializes in regulatory management.

On March 25, six doctors from New York City hospitals, as well as officials from New York City’s Economic Development Corporation, visited the Boyce facility to see a demonstration of the Spiro Wave. At that point, New York State had effectively been locked down; between March 14 and March 31, the city would go from two COVID-19 deaths to 1,000. Doctors were already starting to panic about a coming ventilator shortage. Cohen says the EDC made a commitment that day to purchase the emergency bridge ventilators. (The official purchase order for 3,000 units was signed on April 6.)

Up until then, the three companies had been “running on fumes,” according to Cohen, “putting capital into something and we didn’t know if it was something we’d complete or not.” That was on top of the emerging economic disaster, where shutdowns were already leading to massive layoffs across industries. While everyone believed strongly in what they were doing, having the commitment from the city gave them all some breathing room.

“We just kind of felt like we were born to do it,” says Powell. “We felt like the money was going to work itself out. The EDC [being involved] gave us the comfort that everything was going to be OK. We didn’t get too bogged down in it because we were partners with the city.”

Early to mid-April: ‘We didn’t really take our foot off the gas’

In mid-April, while Varanelli was writing submissions to the FDA, the team at Boyce continued to work on the device. Botha says they made another 12 improvements before receiving Emergency Use Authorization from the FDA on April 17.

Even after the FDA granted the Spiro Wave EUA, Botha says they still did three more rounds of “feature integrations” to keep incorporating the doctors’ feedback and get it where they wanted. “We didn’t really take our foot off the gas for another 30 to 60 days after the EUA,” he says. “That afforded us the ability to look further ahead: How will this product serve the world beyond just COVID? How can we get full FDA approval?”

Late April and beyond: ‘It was like being in a boat and realizing you had three extra rowers’

At the end of July, the 3,000 Spiro Wave devices were delivered to the city of New York to go in its emergency stockpile. While doctors had been clamoring for the device, Cohen says his team opted to keep fine-tuning the ventilator unless there was “a dire emergency.”

For Boyce’s Powell, the project underscored the value of small, nimble companies. “We did this all below the radar,” he says. “I imagine going to GM or Ford and trying to get their factories to change, it’s a major undertaking. It’s like big ships being asked to navigate in narrow rivers. That’s not their nature. We were done before they started.”

For Cohen, meanwhile, the work on Spiro Wave reinforced the entire mission of Newlab, which was founded on the idea of creating a collaborative network that could reinforce one another’s work. “It was like being in a boat and realizing you had three extra rowers and not knowing where they came from,” he says. “We had zero intention on March 15 that we were going to start Spiro Wave, and on March 17, things started just cranking.”

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.