Climate change has already reshaped the world’s most extreme landscapes. As glaciers recede and permafrost melts, the signs of what’s to come are worryingly visible.

But these places don’t just have to be cautionary tales. A new exhibition in Berlin suggests that architecture can coexist with the extreme landscapes of a changing climate, without itself exacerbating the changing climate that’s making these landscapes so extreme. And these remote projects might just be models that other buildings in more populated places need to follow.

The exhibition, Arctic Nordic Alpine: In Dialogue with Landscape, focuses on projects by the Norwegian architecture firm Snøhetta, which has designed high-profile buildings from New York (the National September 11 Memorial Museum Pavilion) to San Francisco (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art expansion) to Shanghai (the under construction Shanghai Grand Opera House). Named one of Fast Company‘s Most Innovative Companies, the firm has also made its mark in the three regions referenced in the exhibition title, designing buildings and public spaces in locations surrounded by permafrost, looming glaciers, and jagged mountains. They’re the kind of places where the impacts of climate change are ever-present. Snøhetta argues that to build in them—and, really, to build in any region affected by the changing climate—architecture must reflect and connect with the natural landscape itself.

The problem is significant. Buildings and their construction account for an estimated 39% of global CO2 emissions. The projects included in the exhibition offer slick visions of how the built environment is bringing its environmental footprint under control, with buildings made of sustainably sourced materials that produce net-positive energy and touch only lightly on the land.

Perhaps the most extreme of these projects is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault Visitor Center in arctic Norway, which is planned to open in 2022. Known as the Arc, the small complex of buildings near the vault’s entrance includes a striking ice-white cylindrical exhibition building that rises from the permafrost like a nuclear cooling tower. Its structural core is designed to be made from cross-laminated timber, the new sustainable darling material of low- and mid-rise buildings. With its temperature set to a constant 39 degrees Fahrenheit, it will serve as a kind of simulation of what it’s like inside the actual vault, which, in order to protect its seeds, is off-limits to visitors.

Farther south is a much smaller and more intimate project that creates a simple observation pavilion from which to look out on the wild reindeer and buffalo-like muskox that roam central Norway’s Dovrefjell mountain range. At less than 1,000 square feet, the stand-alone rectangular steel building holds just a smoothly carved wooden seating area and a suspended fireplace before a window wall looking out on the landscape.

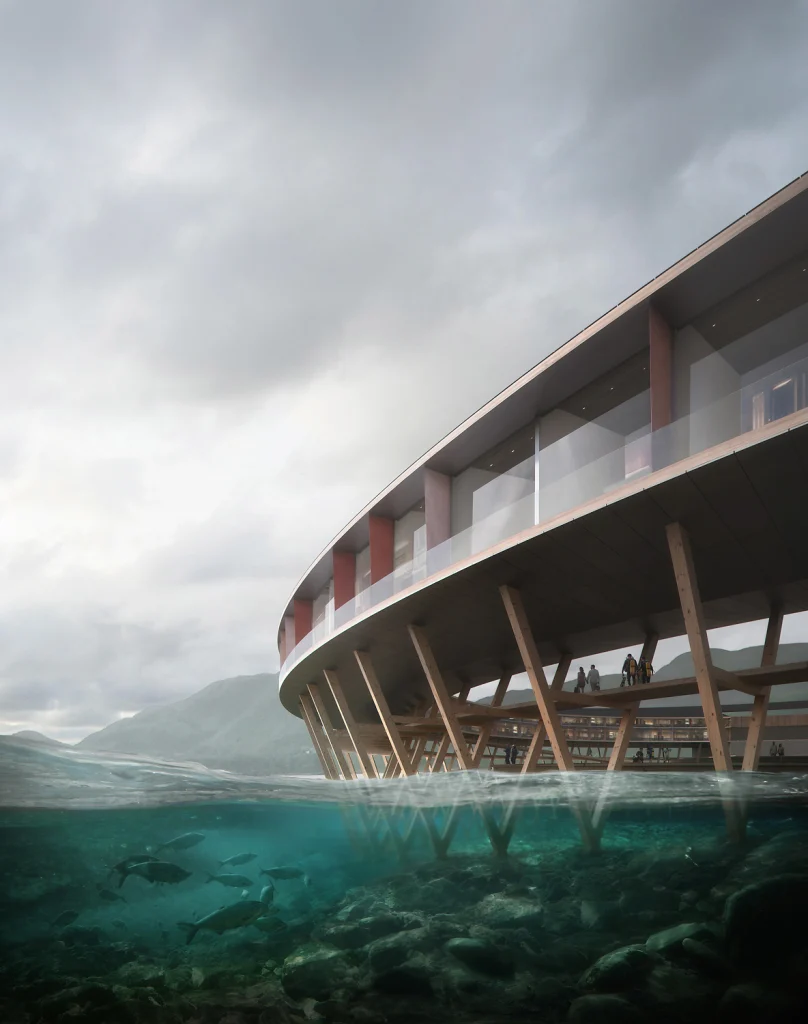

Restraint is a recurring theme. In many cases, the right thing to build is nothing, the firm notes in the exhibition’s catalogue. But “for the places already under pressure, it will be vital to provide facilities preventing further destruction.” That can be a simple room to view a mountain range or a self-powered ring-shaped hotel only accessible by boat.

For Snøhetta, these projects are as much about experiencing vulnerable landscapes as they are about protecting them while they continue to evolve. If architecture can coexist with ecosystems as fragile as the Arctic or a Nordic fjord or an alpine mountain range, surely it can do so in regions that are still relatively unscathed by climate change.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.