New successes in printing vascular tissue from living cells point to the accelerating pace of development of 3D-printing tissue — and eventually the ability to manufacture organs from small samples of cells.

Late last month Prellis Biologics announced an $8.7 million round of funding and some significant advancements that point the way forward for 3D-printed organs while a company called Volumetric Bio based on research from a slew of different universities unveiled significant progress of its own earlier this year.

The new successes from Prellis have the company speeding up its timeline to commercialization, including the sale of its vascular tissue structures to research institutions and looking ahead to providing vascularized skin grafts, insulin-producing cells and a vascular shunt made from the tissue of patients who need dialysis, according to an interview with Melanie Matheu, Prellis’ chief executive officer and co-founder.

The creation of a vascular shunt made from a patient’s own cells should increase the chances of the procedure working successfully, says Matheu. “[If] that shunt fails there aren’t many other options… and then people have ports put in their chest.” The proposed treatment from Prellis could increase quality of life and longevity of people who are waiting for a kidney,” according to Matheu.

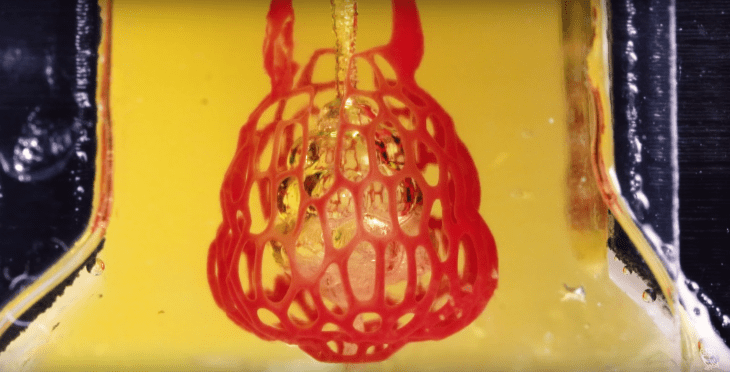

A few months earlier, a team of researchers led by bioengineers Jordan Miller of Rice University and Kelly Stevens of the University of Washington (UW) with collaborators from UW, Duke University, Rowan University and the design firm Nervous System revealed a model of an air sac that mimicked the function of human lungs. The model could deliver oxygen to surrounding blood vessels — creating vascular networks that mimic the body’s own passageways.

“One of the biggest road blocks to generating functional tissue replacements has been our inability to print the complex vasculature that can supply nutrients to densely populated tissues,” said Miller, assistant professor of bioengineering at Rice’s Brown School of Engineering, in a statement. “Further, our organs actually contain independent vascular networks — like the airways and blood vessels of the lung or the bile ducts and blood vessels in the liver. These interpenetrating networks are physically and biochemically entangled, and the architecture itself is intimately related to tissue function. Ours is the first bioprinting technology that addresses the challenge of multivascularization in a direct and comprehensive way.”

Miller has launched a startup to commercialize the research called Volumetric Bio. While the researchers have made their findings freely available through open source licenses, they’re hoping to commercialize the technology by selling their bioprinters and materials and reagents.

The technology that Miller and his team develops uses photoreactor chemicals that respond to light, so specific areas of liquid solidify while others can be rinsed away. The problem is that most of these chemicals have been found to cause cancer, so Miller and his team found a replacement to the traditional photoreactors in an unlikely place — the supermarket aisle.

The researchers surmised that food dye might do the trick and Miller just went to the supermarket and picked up a dye that’s typically used in baking, according to a story in Scientific American.

“We were screaming with joy, because it was stunning how simple an idea it was; it immediately enabled us to make this dramatically more complex architecture,” Miller told the magazine.

Prellis has made significant strides of its own. Alongside the funding, the company announced the successful implantation of tumors in animal subjects that were made using the company’s vascular scaffolds. The target market for these tests is in drug discovery, where animal testing can prove the efficacy of new treatments before they’re used on people in drug trials.

The printed structures, a combination of living cells and hydrogels, are designed to provide a sort of scaffolding that an animal’s own cells can build on. In the study, conducted at Stanford University, Prellis was able to fully graft a tumor onto an animal using just 200,000 cells — far fewer than what’s required for typical tumor studies, according to the company.

And, as the company noted, within eight weeks, researchers identified branched vasculature of up to 50 microns inside the transplanted structures, which indicated the animal’s vasculature system had incorporated the scaffolding into its own circulatory system.

Prellis is actually pitching its pre-made vascular scaffolds to researchers for their work on 3D printed biologics. Scientists at pharmaceutical companies and universities including UC San Francisco, Johns Hopkins, UC Irvine, and Memorial Sloan Kettering, are developing tests with standardized tissue structures (something that’s important for drug trials).

The drug discovery applications alone are a multibillion-dollar market, says Matheu, but the company is focused on its goal of fully transplantable 3D-printed organs, starting with kidneys. The company is going to do their first large animal studies for organ implantation by the end of the year.

“My goal has always been and will always be that we want this to cost the same amount as procurement from a human donor,” says Matheu.

As Matheu looks ahead to the places where more work needs to be done, she points to getting a supply chain to source the right cells for drug therapies and organ development.

So the roadmap for new products begins with the vascular scaffolds, runs through vascularized skin grafts and developing insulin-producing cells and vascular shunts for dialysis patients.

“Regenerative medicine has made enormous leaps in recent decades. However, to create complete organs, we need to build higher order structures like the vascular system,” said Dr. Alex Morgan, principal at Khosla Ventures, in a statement. “Prellis’ optical technology provides the scaffolding necessary to engineer these larger masses of tissues. With our investment in Prellis, we’re supporting an initiative that will ultimately produce a functioning lobe of the lung, or even a kidney, to be used in addressing an enormous unmet global need.”